Planetesimal

The notion of our isolation in the universe positions human beings as the only intelligent, civilised life forms capable of collaborative imagination and self-reflection, and the earth as the only planet that we know of that can support the development of life. The search for living things on other worlds is a practical curiosity - understanding the necessary interaction between an organism and its environment may enable us to gain a deeper understanding of ourselves. There are also lofty ideas that we may resolve fears of ecological disaster through exploring space - terrestrial solutions or indeed habitable worlds to escape to. In a more existential sense it may be a reach for something else, someone else, out there in the darkness. Until that happens however, the near cosmos offers little in the way of neighbourly entities that we can feel a true connection to.

The most widely accepted giant-impact theory details a collision that resulted in the collection of debris in orbit around the Earth, which eventually formed the Moon. Like the fission and accretion hypotheses, it suggests a kind of geological kinship between the two, supported by their shared internal structure - differentiated into a cool crust, mantle and a metallic core. Without the means to make links on biological terms, the routes through which we find our celestial family follow exogeology, shared history and compelling, conceptual philosophy.

Planetesimal is a sculpture that encapsulates these ideas, fusing them through a design-led artistic research process that relies on finely tuned fabrication techniques. Its origins lie in a fascination for celestial bodies, their peculiar characteristics and the way light plays over their surfaces. This detail became a point of interest in itself, and over the course of its early development transferred focus to cratered asteroids. Of approximately one million known asteroids, a particularly intriguing example became the subject of the piece.

In contrast to the familiar sight of the Moon, 4 Vesta sits at an incomprehensible distance of 100 million miles from earth, in the main asteroid belt that exists between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter. With the naked eye the moon can be experienced closely enough to sense its mass and marvel at its surface, whereas Vesta, if sighted at all, will only appear as one of myriad pinpoints of light in the night sky. It is the second largest asteroid in the belt after its sister Ceres, classified as a dwarf planet.

Vesta and Ceres were the primary exploration targets for the spacecraft Dawn, which launched in September 2007. The main goal of the mission was to uncover information that could help us understand further details about the formation of the Solar System. In 2011 it reached Vesta where it began to survey the asteroid from orbit.

Vesta was found to be somewhat unique. In contrast to Ceres, which is largely composed of rock and ice, Vesta’s differentiated interior comprises a metallic iron–nickel core and a silicate mantle that has cooled to form a rocky crust. This makes it something of a rarity, bringing it in line with the terrestrial planets and aligning its internal structure with Earth and the Moon. It also suggests that it was formed at an early stage of the Solar System’s development - within one or two million years of its birth and before the formation of the planets. Managing to avoid collisions that have decimated similar bodies, Vesta has survived and exists as a preserved relic of a young universe.

Dark and light patches on its surface suggest historic lava flows, and the craters tell of a vicious shared history. Like the terrestrial planets Vesta was hit by a large number of asteroids and comets during the lunar cataclysm. Craters are comparable to those found on the Moon, and that have been mostly erased on Earth due to erosion and tectonic activity.

On Vesta’s southern pole is the Rheasilvia Basin, one of the largest craters in the Solar System, and contained within it a central peak rising 14 miles from its base, competing as the highest mountain in the Solar System. The massive impact that created this crater ejected material that formed the Vestian asteroid family, and Howardite–Eucrite–Diogenite (HED) meteorites. A large number of these have reached Earth, and have been found to closely resemble earth’s terrestrial magmatic rocks. Despite its distance from us, the discoveries made by the Dawn probe bring Vesta figuratively closer to us, lessening the abstract nature of galactic speculation that usually holds matters of the cosmos out of reach.

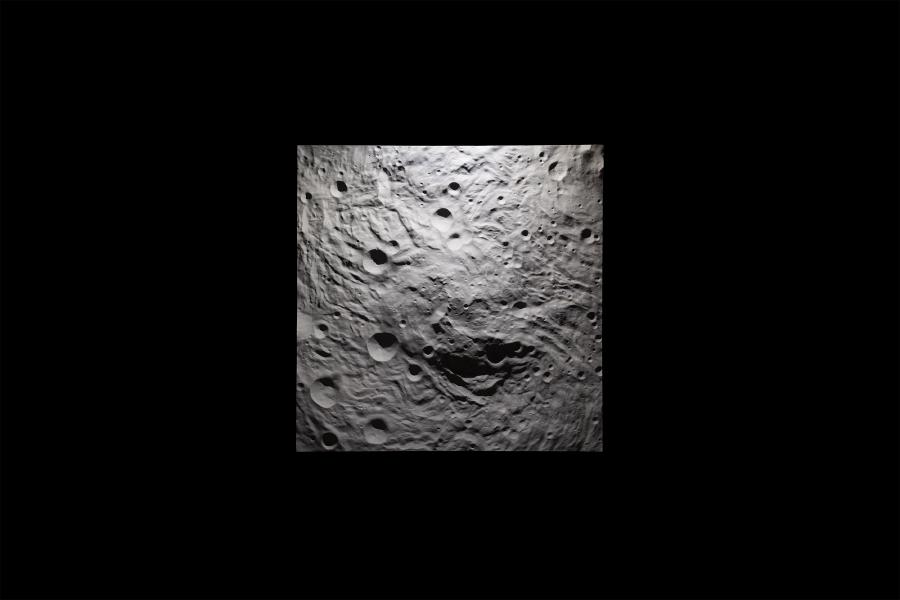

A 500 km section of Vesta’s Rheasilvia Basin is the focal point for Planetesimal, rendered in plaster with meticulous accuracy and representing a physical manifestation of topological data gathered on the Dawn mission. In sharp contrast to the organically formed surface, the outer edges of the plaster form a perfect square when viewed face on, outlining the unnatural nature of extracting, with such precision, a section of an asteroid’s surface.

Cradling the work is a deep black steel frame, a void in which the sculpture is suspended, pushing the artwork back into the expanse of its origin. In an artistic sense it anchors it to familiarity in the way it is presented. The frame neutralises the backdrop onto which the rendered crater is set, a rendition of deep space; the surround is set forward from the centrepiece, slightly shielding it from ambient light.

This latter detail helps emphasise a key aspect of the piece which turns it into a living artefact, and connects to early ideas involving how light exposes the structure of impact craters on celestial bodies. Hidden within the frame is a halo of LEDs programmed to gradually revolve a point of directional light over the primitive surface. Activating the work in this way augments the detail oriented physical structure with a behaviour that gives it life.

Planetesimal is a piece of work that takes a central source of media - data - and uses it as a sculpting instrument that is as much a valid part of the creative process as a painter’s pigment design, or a ceramicist’s modelling tools. Through precise machining this data recreates something truly awe inspiring in the physical dimension, turning it into an art-object that we can see and touch. Stripped of all detail save for the contours of its geology, the plaster moulding is an expression of minimalist design. The particular plaster has been chosen for its stark brightness and hardness, reproducing gigantic measurements into fine details that are quantifiable to the human eye and mind. It is cold to the touch, utilising even temperature to convey the otherworldly domain of the entity it simulates, and possesses a graininess that stops it short of overly sterile refinement.

The starkness of the inversely toned frame is assisted by a coating of satin black spray paint, resistant to anything but the most subtle reflections. Formed in heavy steel, an erasure of known reality through which a captured ghost of Vesta hangs.

LED lighting applies an element not often seen in any artwork - evolving, cyclical time that exists external to the ways humans have divided and utilised it. The time it takes for the light to complete one cycle across the surface of the plaster is four hours - the same as the time taken for Vesta to make one rotation. The light itself is a daylight white, chosen to avoid adding any unwanted colour to the bright plaster, which is itself homogeneously white, leaving every surface detail an unaltered result of NASA’s data. In collaboration the data and light invoke clean, crisp detail, aligning the profoundly natural with the coldly procedural.

In reducing components down to their most minimal form, and refining these to a point of aesthetic and conceptual harmony, the wordless, ethereal qualities of the piece are elevated.

Vesta was the fourth asteroid to be discovered, and the second by Heinrich Wilhelm Olbers. It is part of a large number of discoveries in the 19th century, during a time of particular stellar investigation in Europe. Olbers named it after Hestia, the Greek goddess of the hearth, household and family, associated with an ever burning fire. This essential fixture for baking and cooking in Ancient Greece is symbolic of care and provision, and forms a clear link to the mantle core of Vesta, itself an unending furnace. Moving from an easily discernible parallel towards something more abstract, we can question whether Hestia and Vesta share a maternal energy.

Hestia’s presence was more often represented by her holy fire, a sacred hearth in the Temple of Vesta, located in the Forum Romanum. She is thought to be one of the oldest of the gods, echoing the ancient origin of the asteroid in our early Solar System. She was rarely depicted in human form. In later philosophy Hestia became the hearth goddess of the universe.

At human scale, and through the orders of magnitude, fire is a source of creation and destruction. Through its violent history, most notably the impact which caused the Rheasilvia Basin, its birthing of further Vestoids and the HED meteorites that have found their way to earth paint a picture of creation as a result of destruction. It is Hestia manifest, not only by name.

Our engagements with the solar system, aside from existing within it, are extremely limited. We have little inherent ability to mentally compute the magnitude of space, and to describe its violence and beauty. The imagery, data and rendered motion graphics that we do have access to can only go some way to detailing the movements and interactions of our galactic home, and our senses, in the limited ways we can consume these, are rarely activated in combination.

For the most part, the majority of human beings experience celestial bodies as specks of light in the dark, processed photographs and, if we’re lucky, interactive animations. There is no experience of proximity and directness. Planetesimal bridges this gap of obscurity into something known, bringing Vesta closer to us, editing the unknowable into human terms. It allows us to witness the sheer enormity of space, as a physical vastness and a chasm of near endless time. A harmony of materiality, light and movement, all backed by research, its performative automata doesn’t just activate our curiosity; it satisfies it too, managing to form a dialogue between the endlessness of the cosmos and the intimacy of sight and touch.

Our obsession with space runs parallel to unending explorative notions of what our existence means to us, complexified by relationships that inspire our scientific and philosophical persuasion. In drawing these together, the piece completes a triad of astronomy, mythology and artistry.